This translates to House of Two. The English language adaptation of Crying Freeman was the cover story for the April 1996 issue of the French Impact magazine, but this isn’t saying that much since the film was directed by a Frenchman. Not only that but it was co-produced by a French company. The feature on Crying Freeman was spread across a dozen consecutive pages, but I’ve edited the article for clarity.

Let’s get the star out of the way first since he only got two pages (three if you include a full page photo). Mark Dacascos explained the beginning of his involvement: “It didn't happen overnight. It was in the middle of filming Only the Strong circa 1993, during a lunch with Samuel Hadida among others, that I first heard about Crying Freeman. The film was still in its embryonic stage. Interested by Hadida's description, I immediately got hold of the comic strip and the animated manga. I loved it. For a little over a year, Hadida and I discussed the project, but its implementation was proving to be long and complex. And I wasn't alone in the ranks. I put all the chances on my side by pushing, me and my agent, with the producer. It was only after a lunch with Christophe Gans that things got moving.”

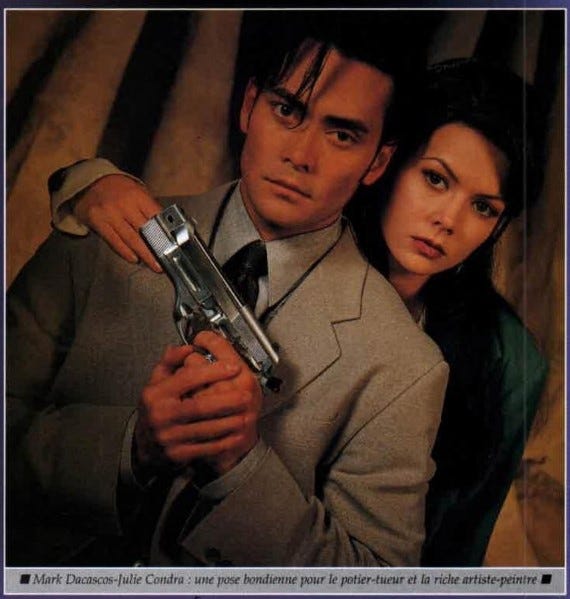

About what attracted him to the story of freeman Yo Hinomura: “The bad guys are not so mean; they show a real sense of honor and thus command respect. The not-so-poor hero is an assassin after all. There are two sides to life, each has its own yin and yang. Nothing is simple. But no one is really all white or all black in Crying Freeman. Christophe Gans prefers the gray, an intermediate stage. As in everyday life! When I read the script, I immediately understood that Yo Hinomura and the Freeman are the ying and the yang of the same individual. Both the potter and the killer had to have the same intensity, the same energy. The person does not change from one sequence to the other, depending on whether they kill or love. Only their behavior adapts to the circumstances. We all act like this, in less extreme situations, however. In front of your parents, you do not behave as if you were in the presence of your girlfriend, your friends or your boss. However, you are the same person. I did not want to let one aspect of Yo's dual personality smother the others.”

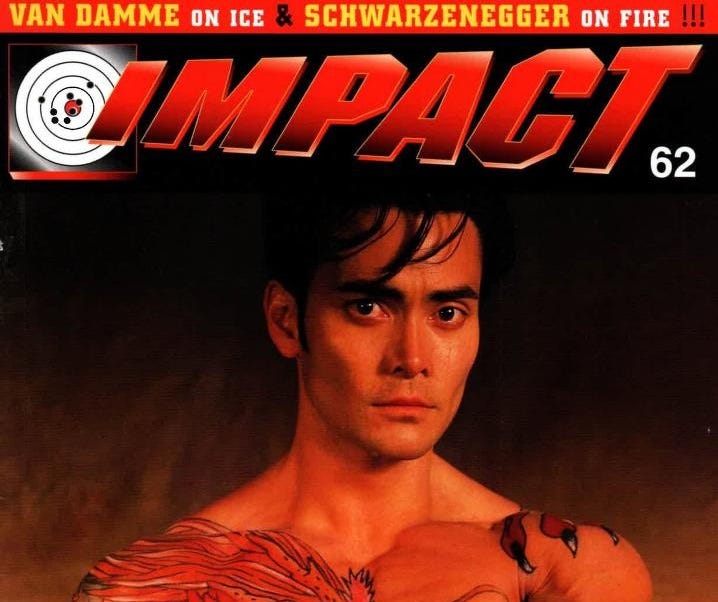

The film was first screened in Toronto circa September 1995. As such, Mark Dacascos said: “Shooting began in late fall and continued into early winter in Vancouver, a city not known for its tropical temperatures. We were often working near zero degrees. It was either snowing or it was raining and frost covered the ground, especially in the forest. Of course, I wasn't wearing a thick down jacket. I was there shirtless, dressed in nothing but silk pants. And Julie Condra, my partner, was covered only by a little dress, also silk. We had to move, act, fight without showing that we were shivering from head to toe. The pace was such that we worked six days a week. The seventh was devoted to a tattoo session that lasted between 8 and 14 hours. We never stopped. It was all so intense, so compact that, when we weren't acting, we talked about our characters. Nothing was easy on the film, not even the most intimate sequence with Julie Condra. We had to spend a week almost naked in a room, with people all around us even though Christophe Gans had only allowed access to the bare minimum of technicians. But I'm not complaining, it was worth it.”

Director Christophe Gans is a major fan of Hong Kong action cinema like producer Samuel Hadida (who has worked with fellow H.K. film fan Quentin Tarantino). In the French Impact magazine, Christophe explained why he didn’t adapt another hitman manga - Golgo 13 (which started in 1968): “Within gekiga, in other words action manga, Crying Freeman tries to reach a wider audience than usual. It is mainly young executives who devour action manga. Crying Freeman, meanwhile, is aimed at both women and men. Women thanks to the abundance of romantic elements, mainly in the first two volumes of the comic strip, the ones I brought to the screen. I was immediately struck by the femininity of the story, including in the very style of narration. Crying Freeman corresponded to my wish to make an action film that women could like. Why? Because it always annoyed me to go to the movies with a friend and hear her say, after the screening, that this is a movie for macho freaks, for Mongoloids, for, in the worst case, repressed homosexuals! Ladies, I have since sworn to wait for you with an action movie that you can like.”

Have no fear, men: “And that does not mean that I have to water down, to delete everything that builds the characteristics of the genre, everything that transmits excitement. Not only does Crying Freeman offer me the possibility to rally women to my cause, but, moreover, it gives me the opportunity to make a variation on the neo-thriller from Hong Kong. Especially The Killer. Without copying it, however, which is not easy when you love a film beyond all else, to the point that you have to cut the umbilical cord that connects you to it, that you have to settle your accounts with this haunting film.”

As for why he was annointed the director: “Kazuo Koike and Ryoichi Ikegami reacted favorably to the script that Thierry Cazals and I wrote based on their comic strip. We had not actually perceived things from a European point of view by trying to imitate an Asian point of view. Samuel Hadida, the producer, then asked me to direct the film. That's when our Japanese interlocutors balked. For them, I knew how to write a script, but to direct a feature film was a mystery and a ball of gum. I had nothing to show them to convince them. At that time, they were putting together a sketch film project with Brian Yuzna based on Lovecraft’s Necronomicon. They had a director for the Japanese segment, Shu Kaneko, a director for the American part, Brian Yuzna himself. All they needed was a European filmmaker. They first thought of Michele Soavi, Dario Argento, before settling on me. They told Samuel Hadida: If you want Christophe Gans to prove himself, let him shoot this Necronomicon sketch!”

It should be noted that Brian Yuzna became the co-producer of Crying Freeman, but that didn't stop Christophe Gans from saying: “More than the other two, it was my sketch, The Drowned, that caught the attention of critics, both in the United States and in Japan. So, seeing in me the beginner who was taking the laurels, Kazuo Koike and Ryoichi Ikegami gave me the green light for Crying Freeman. I would never have gotten it made if I had failed in Necronomicon. No producer would have risked $9 million on my good looks. Even if it is not a big budget, it is still a sum for a first feature film! In fact, Necronomicon was the carrot for Crying Freeman - a real passport.”

Christophe Gans reveals a film-making technique: “During the writing of the screenplay, Thierry Cazals and I spent a lot of time thinking about the question of tears compared to Yo's split personality. To really highlight the metamorphosis of the kind potter into a ruthless assassin, I took the initiative to change the color of his eyes after he transformed. Extremely discreet, but it counts for a lot. The contact lenses completely change Mark Dacascos' face, age him by ten years, and give him an extraordinarily hard appearance, mainly in the sequence where he points his gun at Emu's temple.”

There is an misconception about how outsiders perceive budgets: “People who see Crying Freeman as a technical feat in terms of budget are blinded by the Hollywood system of financing, an inflationary system. It's not my film that costs less than it seems to them, but their films that cost too much. Crying Freeman was budgeted precisely for what it was supposed to cost, with the usual margin of error that every shoot involves. There's nothing fantastic about it whatever but some people say “Christophe Gans made a thirty million dollar film for nine million.” I hear that so often! It's not Crying Freeman that constitutes a performance, but blockbusters like Cutthroat Island, $110 million, that are wrong! Crying Freeman at least shows that it is possible to produce action films full of gunfights and explosions for a reasonable price.”

Investing wasn’t all sunshine and rainbows: “Of course, I would have appreciated a few extra days, a financial extension, but I realize that in putting pressure on me to meet deadlines and stay on budget, Brian Yuzna was absolutely right. He knew how to wrap up such a production in just 40 days, despite the abundance of action scenes, despite the imposing logistics. Hollywood studio executives do not react in the same way. I noticed this when meeting Universal executives who offered me an immediate deal for two titles. A scene that I shoot in half a day takes a major director three days of work. Why? Because he covers the shot in 360 degrees - he films it from every possible and imaginable angle. This filmmaker provides material that will be used to re-edit his film if it does not satisfy the producer, or in favor of reactions to test screenings.”

As a John Woo fan, he had to have been reminded by Universal’s Hard Target (1993) since even editor Bob Murawski (an employee of producer Sam Raimi) noted that Woo never shot more than what was necessary. Christophe Gans went on to say: “By ordering the director to collect as much film as possible, the studio executives cover themselves because, constantly, they tremble at the idea of losing their job. They protect their backs! It is paradoxically easier to put together a $70 million project like Assassins than an average production. Despite the flop of Assassins, executives can say, “But yes, there was Stallone, Richard Donner. Normally, Assassins should have worked.” Famous names legitimize commercial failures. On the other hand, if a much more modest production flops and there are no famous people in its credits, you have no excuse - no way to justify yourself. I strongly believe that there is only one angle from which to film a shot: the right one. This is a precept that Sam Peckinpah believed in. He said something like: “There is only one camera axis to capture the soul of a sequence.” I more than agree with him.”

lt’s no picnic dealing with small fries. If only a Taiwanese investor or an incredibly rich Jew got involved: “The relatively modest budget did not offer me plane tickets to the four corners of the world. So I had to stay in Vancouver, including for the sequences set in China and Japan. Crying Freeman allowed me to travel through my cinephile memory. It was up to me to travel through my memories by reconstructing the foreign sequences to give them maximum authenticity. These scenes were done in a style that exactly matches the country where they are supposed to take place.”

Sometimes a bigger budget means a bigger salary, or more money spent on marketing if you have someone with marquee value. Jason Scott Lee was the first choice for the role: “Even if its budget would have remained within the realm of reason, I would have been more exposed. If you keep below the symbolic bar of ten million dollars, you don't risk anything. If your film is not released in theaters in the United States, no one will hold it against you. In filming Crying Freeman with Jason Scott Lee, I would have crossed this bar. It would have significantly increased the pressures and multiplied the compromises. The fact that he could not free himself from a contract saved my behind. As for imagining what the movie would have been with Jason, it's not very difficult. Crying Freeman was very different from the film. I saw the manga as a real Asian James Bond. He was oriented more towards incredible missions than towards a gang war. The action sequences there were truly colossal. Crying Freeman with Jason Scott Lee would have been a bigger movie than it currently is.”

JSL was wanted in 1992 after he had completed filming Dragon: The Bruce Lee Story, hence Christophe Gans saying: “Three years later, Mark Dacascos filmed the role. He is absolutely unrivaled in the field of sound character interpretation. Jason Scott Lee was prodigious as Bruce Lee but he could not have accomplished everything I had envisioned on paper. We would have had to use stunt doubles. With Mark Dacascos, I was incredibly lucky to have an actor who really looks like the manga hero, who shares his beauty, and an actor who is also an athlete capable of all the physical feats, capable of equaling, even surpassing, the exploits of this character in the comic strip. Unique! You have to go back to Bruce Lee to find someone who is able to take on the challenge of the feats that a script demands of an actor. I'm not talking about Jackie Chan who is more of a clown, from the burlesque tradition, who plays on his unattractive physique to gain support of the public.”

Like John Woo, Christophe Gans is a fan of French screen icon Alain Delon, thus Mark Dacascos is compared to him: “His resemblance to the Alain Delon of the sixties, of Le Samourai, struck me. This Delon era is the very incarnation of Crying Freeman. When I first discovered the comic strip, I said to myself “But it's Delon in Antonioni's L’Eclipse!” This is no coincidence since, in the 60s/70s, Delon was a megastar in Japan. He therefore naturally inspired the manga's illustrator, Kazuo Koike, just as Jennifer Connelly (in spite of herself) served as a model for Emu O'Hara - his fiancée.”

As for whether Brandon Lee would have been cast if not for his untimely death, Gans said: “Quentin Tarantino, whom I know through Samuel Hadida (who distributed Reservoir Dogs in France), and Roger Avary (whose Killing Zoe was produced by Samuel Hadida), appeared one day in my office. With his usual flow, Quentin threw at me Brandon Lee as the freeman. He had just seen this Rapid Fire dud in which Brandon Lee was actually not bad at all, although not really valued by the director. I have some difficulty in bringing Brandon Lee closer to the character of Crying Freeman. Nevertheless, I admit that I sold my film to certain foreign distributors and to my technical team by presenting it as a light version of The Crow, a film from which I borrowed the artistic director, Alex McDowell. Light because it’s far from its filth, its permanent darkness. But, like The Killer, I wanted to go against The Crow, to engage in another direction while admitting its influence on me.”

For all of its romantic intentions, action was the order of the day (especially when you want to raise money by showing footage to financiers) as Gans said: “Samuel Hadida, the producer, asked me to shoot gunfights, explosions, chases as a priority. Usually, we start slowly, with dialogues, to gradually get into the swing of things. I had a serious baptism of fire! David Wu and Bill Gereghty brought me a lot. The former had the talent of someone who has edited some 350 films since Chang Cheh's The New One-Armed Swwordsman.”

Christophe Gans appears to have learned something about the Wong Jing method: “Normally, Crying Freeman could not have been completed in forty days. Too many different sets, too much action, too many stunts, too many gunfights. How to overcome this obstacle? By working simultaneously with two teams, the very key to the success of the film. When you only employ one team, the slightest trip to another set takes on the appearance of a move, with trucks, dismantling of equipment. To avoid this considerable loss of time, we set up this second team led by Bill Gereghty - Sam Peckinpah's assistant since Convoy until his death. As soon as he told me he had collaborated with Peckinpah, an angel came by. I put him on a pedestal. He generally does not receive more consideration than a simple worker. The feeling of having a real position inside a film, having a real dialogue with the director really pumped him up.”

Things come full circle to the Hong Kong film influence: “And Bill Gereghty gave a lot to Crying Freeman, while having a blast. Not only did he respect the storyboard, my instructions, but, moreover, he brought little somethings that were invaluable. In fact, with him, I benefited from what John Woo had found in Ching Siu-Tung on The Killer, someone who filmed according to the instructions while taking initiatives - bringing ideas for shots. Bill Gereghty understood my style perfectly and brought his experience. I attach a lot of importance to his precious collaboration because alone, you could never make a film. It is rigorously impossible, regardless of what these pamphlets on the politics of auteurs claim. The filmmaker does not work alone, there is a team around him, a tribe in which he imposes himself as leader.”